Keelboat Docking - Part 1 - Planning and Preparation

Introduction to the Blog Series

Docking our keelboats under sail is one of the most difficult skills required for the Senior Rating. You have to be able to do it in all wind directions and in several boat types that handle very differently. It takes a huge time investment and a lot of commitment and practice to make the grade.

Everything you've learned on dinghies applies to keelboats, and on dinghies you establish a solid basis of sailing skills. This is why we require a Junior rating to take keelboat lessons, and why it's important to get your Senior Dinghy test passed before getting serious on keelboats.

But the transition from a dinghy to a Pearson Commander is not easy, as the latter has a large mass and a full keel, so it handles very differently from a dinghy. It does everything slowly, including stopping, but also powering up. If you get below the critical speed for steering it, it can take 8 or 9 seconds for the keel to power up, and in that period you're being pushed sideways. You could end up pressed against a downwind piling or boat.

Our keelboat slips are faced approximately west, so normally into the wind, just like our dinghy dock in the South Sailing Basin. So in a "normal" west or south-west wind, you dock pretty much the same way. Slow sail on a close reach into the dock/slip. But the boats are very different, so the procedure becomes more challenging on a keelboat, not to mention the damage you can do if you screw up.

This is the first in a series of blogs on keelboat docking to help you understand the differences between dinghy and keelboat and the additional factors that become important with the latter. I will assume a "normal" west or south-west wind, as this is what you'll be dealing with 80% of the time, at least. And initially, I'll be assuming relatively constant wind, although later in the series I'll talk about wind shifts and how to deal with them. I'm also assuming that you're planning to go into one of CSC's docks with a reasonable amount of time to prepare and plan. As you get more advanced, you will be required to do very quick impromptu dockings, but that comes much later.

Planning and Preparation

In a sense, the most important part of docking happens as you're coming into the Marina, or maybe even before you enter it. You, your boat, and your crew must be ready. I've seen students heading for the final turn with completely unprepared crew and lines not ready, and maybe even no clear idea of what they're going to do. This is a recipe for disaster.

These are the key items:

- What's the true wind, and based on that, how are you going to dock?

- What's your bailout point and your Plan B, Plan C?

- If the boat needs to be reconfigured before docking (e.g., drop the main, the jib, or both), where are you going to do that? Each person involved should know exactly what their job is, including preparing the boat (getting halyards and sail ties ready, for example).

- All docking lines must be ready for use and laid out so that they can be used quickly and easily.

- Crew must understand how you're going to dock and what their jobs are, including how to step off and stop the boat.

- Crew must also understand your Plan B and their job in it.

1. True Wind

Docking is one of the few times in sailing where you care about the true wind instead of the apparent wind. How you choose to dock depends on what you expect the true wind at the dock to be when you get there.

You have lots of clues to this as you're coming into the Marina. The direction of the seas outside the Marina is one, as it's aligned with the recent average wind direction. But note that it's not sensitive to wind shifts and takes some time to adjust after a major wind shift.

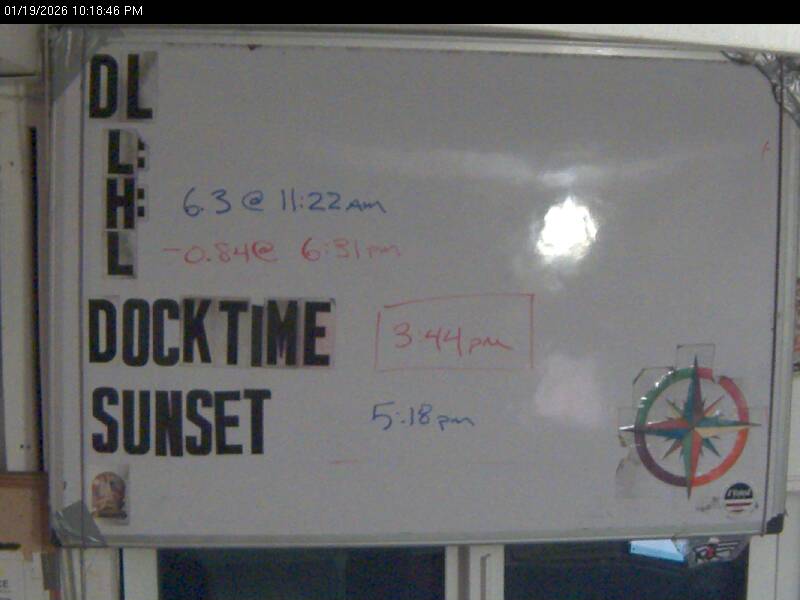

As you come down the fairway, you'll see flags in the Marina and the masthead vanes of docked boats. The closer these are to the dock you're going to, the more likely they are to represent the conditions there. Wind speed and direction vary in the Marina due to the objects on land, such as buildings and trees.

If you're sailing on a run, note your course when the jib starts to back, as that's dead downwind.

Finally, you can swing the boat in the turning basin into the wind to see where the jib goes over the center of the boat as does the boom. At that point, you will be pointing directly into the true wind.

In this series, we're assuming "normal" West or South-West winds for a docking, but in different winds, you will have to dock differently. This a good reference for the options. The key point is that you need a plan based on the wind way ahead of the docking itself.

2. What is your bailout point and your Plan B

Having a plan is a must, but you may not be able to execute it for various reasons, including wind shifts at the last moment or maybe mistaken judgement. In any event, you need a Plan B and a decision point. The decision point is where you decide whether you can make the dock safely, and if not you have the speed, and therefore maneuverability, to get out of there safely.

There is no shame in aborting a docking and going around and doing it again, in fact is shows good sense. And you should not feel so good eeking one out just barely, as slightly different wind conditions would have led to a worse result.

The details of the bailout and Plan B depend on a lot of factors, so I won't discuss them here. I will discuss it for the "standard" docking later in the series.

3. Boat Reconfiguration

You may need to drop sails for the docking. In the "standard" docking to a West or South-West wind, you generally don't need to do this. But in a reasonable wind, you might drop the jib to avoid flogging your crew with the jib sheets in the approach, especially with jibs larger than 75%. But consider this. Having the jib down is nice if all goes perfectly, but the drawback here is you have now limited your resources and the ability to maneuver out of a failed attempt. So it's a trade-off, like a lot of things.

If you decide to reconfigure, it should go like clockwork. You prepare your crew by describing the maneuver, preparing the halyard to run, decribing each person's role in the maneuver, and then executing it. There is no need to rush it, assuming you provide plenty of time and space by a good choice of when and where.

It is absolutely essential that each person involved understand their role, and how and when to do it. Your job is to control the boat, watch for traffic, and direct the maneuver. There's no need to rush it, and if it doesn't go like clockwork, you have time and space to correct it.

4. Dock Lines Ready for Use

Fenders also. These should be set early so you don't have a scramble just before the dock. The lines should be laid out so that they are available instantly for use, for example the bow lines run outside of the pulpit and the shrouds, stern lines laid out outside of everything, both ready to be grabbed and used by the person stepping off the boat. If you're using a "stopper line" or brest line, have that ready to go also. The skipper should always have bowlines and stern lines laid out on each side, port and starboard, even if your plan is, for example, to dock on port; this gives you an added ready option, if things go awry and you ‘dock’ instead on a neighboring boat, or in a slip far down the fairway, on starboard.

5. Crew Must Understand What to Do

Explain briefly how you will drive the boat into the slip and what they should do and at what points. Usually, they're stepping off the boat and stopping it when it gets into the slip. The best time to show how to stop the boat is on the dock before you leave, as you can demonstrate it with the boat.

Also, the crew must understand that you might not do a perfect docking. Ideally, they step out at the shrouds, but if you don't make it far enough into the slip, they'll have to go forward and step off there. And if you stop completely short of the slip, they might have to fend off (with feet, not hands).

6. Crew Must Understand Plan B

At least minimally, in that you may abort the docking and bail out in some way. You don't want to surprise them, and you may need them to help in the bail-out. So, brief them on how this might happen and what they need to do, if anything. And you might tell them that a bail-out is a normal thing in response to changing wind conditions or human imperfection at the dock, which it is.

Next Blog

Next time, I'll discuss how to set up an approach for the standard docking (West or South-West wind), with a special discussion of Sheldon's correlary to Einstein - "Space is Time."

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments 2

Great post! Looking forward to the series. I wanted to reiterate this part:

"Finally, you can swing the boat in the turning basin into the wind to see where the jib goes over the center of the boat as does the boom. At that point, you will be pointing directly into the true wind."

What I see a lot of people do is spin the boat up into the wind until the main luffs, and go 'ok, there's my slow sailing angle'. The problem is this shows the apparent wind, but not the true wind, and true wind is more important when determining a slow sailing course. What happens is, when you turn into the wind until the main luffs, you're usually still going pretty fast. So, you determine that to be your angle then you fall off and head for your docking. But as you approach the dock, and start slowing down, what happens to the apparent wind? As you slow, it starts to move back, and now what was a good slow sailing angle is starting to be a beam reach, and the main starts powering up and you can't slow down any more for your docking. Now you have a problem. I hope you've already figured out your Plan B :-)

The only time apparent wind is the same as true wind is when directly head to wind (boom and jib center), or on a run (jib starting to cross the boat), which is why we use those specifically as checks. (The other time both apparent and true are the same is when the boat isn't moving, but that's not the best way to get a gauge on true wind while sailing).

Note: You also have this same concern on dinghies, and I see people power up as they slow down, but it's less of a concern, as you usually have more room to just head up and adjust where you dock, and it's also just a dinghy. On a keelboat you really only have one place to go, so you better be able to slow down the whole way there...

Excellent point, Ryan. I think that why this isn't so much a problem in dinghies is that they're usually going slower when they do the wind check. Also if you get a really big luff in the sail, it will give you some more margin to cover the true/apparent wind difference.

I would recommend to readers to think through carefully Ryan's point, with wind diagrams even.