During the summer months or during the addiction-satisfying winter storm sailing, you can often find yourself overpowered. I’ve also heard of this several times during senior tests where the tester “falls” overboard for the legendary single-handed man overboard, occasionally where the tester is “unconscious”, typically in something like 20 kts. As the wind comes up from a comfortable 10 kts, the full sailed Bahia and JY will begin to require a bit more leverage than hiking out supplies, depending on crew weight. This is the beginning of the wind range that requires, or at least benefits from, using the trapeze. If you’re comfortable with your crew and/or your ability to drive the boat, start to use this. It’s a lot of fun to trapeze while single-handing and is arguably the most fun you can have without flying the kite, but be prepared to swim on your first few outings.

As the wind increases further to the over 15 kt range, the challenge really starts to kick in. Depending on your and your crews weight and skill, you'll need to consider various ways to depower, the most obvious being reefing. If you're luffing your sail more than not, you should be reefed. Another way to depower your main sail, is to pull on your cunningham. As the wind comes up, you should also use your vang/gnav to flatten the sail and change the placement of your draft in balance with your additional cunningham. This is the standard sail trim and depowering technique. As you struggle to keep the boat powered and moving, you can start to ease your jib a bit. This has the tendency to twist off the top of the sail and allow the boat to breathe a little bit by opening the slot between your main and jib. Closing this slot is what causes the “speed bubble” in the main, due to the wind coming off the jib backwinding and the main. As you’re “more” overpowered, you can ease your vang/gnav to twist off the top of your main sail.

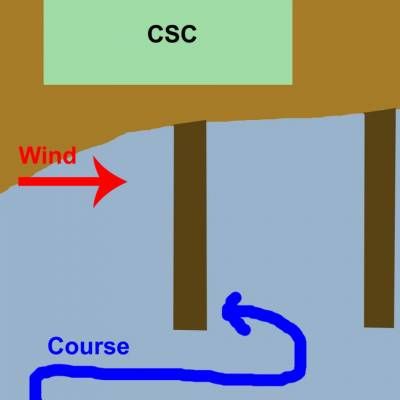

One of the things that I haven’t seen done often at CSC is changing the placement of the centerboard while sailing. It’s commonly thought, at least at first that your boat is “under control” if it’s upright, but in reality, your boat is only under control when you are able to make headway and able to maneuver in some capacity. For this reason, I suggest that when extremely overpowered (repeatedly capsizing or completely luffing), you try raising your centerboard a bit. If you look at the diagram, you can see that as the length of the centerboard is reduced, you allow the boat to slip sideways more, but at the same time, you’re reducing the rotational torque that it’s causing on the boat by reducing both its lever arm and area. This allows the boat to slip sideways more but also reduces the leverage and reduces the heeling “force.” Although you may immediately argue that this is hurtful to your ability to get upwind, it allows you to trim your sails as opposed to luffing. When your sails are luffing, the only force on them is to leeward. However, once your sails are trimmed and have some proper shape, you have a driving force forward. For this reason, it is best to trim your sails to your course, then trim your weight and centerboard to match each other in their torque (rolling force) on the boat. As the boat increases in speed, your centerboard will create lift, which will “lift” you to windward. This lift is proportional to your speed, so as your boat speed increases, your leeway will reduce dramatically. This is much preferred over the scenario where the overpowered boat drifts sideways and you can’t sheet the sails without risk of immediate capsize.

In other words, if we focus on the rotation portion, the torque counteracting the wind and water comes from the crew weight (or the lead at the bottom of the keel in a keelboat). Torque is force multiplied by length, so getting your weight out of the boat more, such as being on the trapeze or hiking, benefits your righting moment dramatically. This is part of the reason sails are lowered when it’s windy, it reduces the heeling force (torque) on the boat. Likewise, you can do this by lifting your centerboard to “reef” your centerboard. This, like a reefing a sail, both reduces the area as well as the length over which this force is acting.

Another important thing that isn’t often mentioned around the club is the region around a beam reach that opens up in (very) high winds, which is affectionately called the zone of death (ZOD). The ZOD arises when it’s too windy to keep the boat upright with all your weight utilized to its limit on a reach. This is basically when you find yourself completely overpowered. In any case, the existence of the ZOD means that you are now limited to only upwind and downwind sailing and not too much in between. This is a result of a beam reach being your fastest and most powered up point of sail. When you’re sailing in winds with the ZOD, your next biggest concern, other than staying upright when sailing in a straight line, is getting between up- and downwind courses. To do this, you must make a smooth and decisive maneuver to bear away. It’s helpful to have your weight toward the back of the boat and have pre-eased the jib. Once downwind on a broad reach, you can relax a bit and steer for heel with the main eased a few feet off the aft quarter and ease in the gusts. The most important thing when sailing in these conditions is to keep the boat moving and flat. Once you have leeward heel, you will likely round up and broach, leading to your next chance to master the bear away.